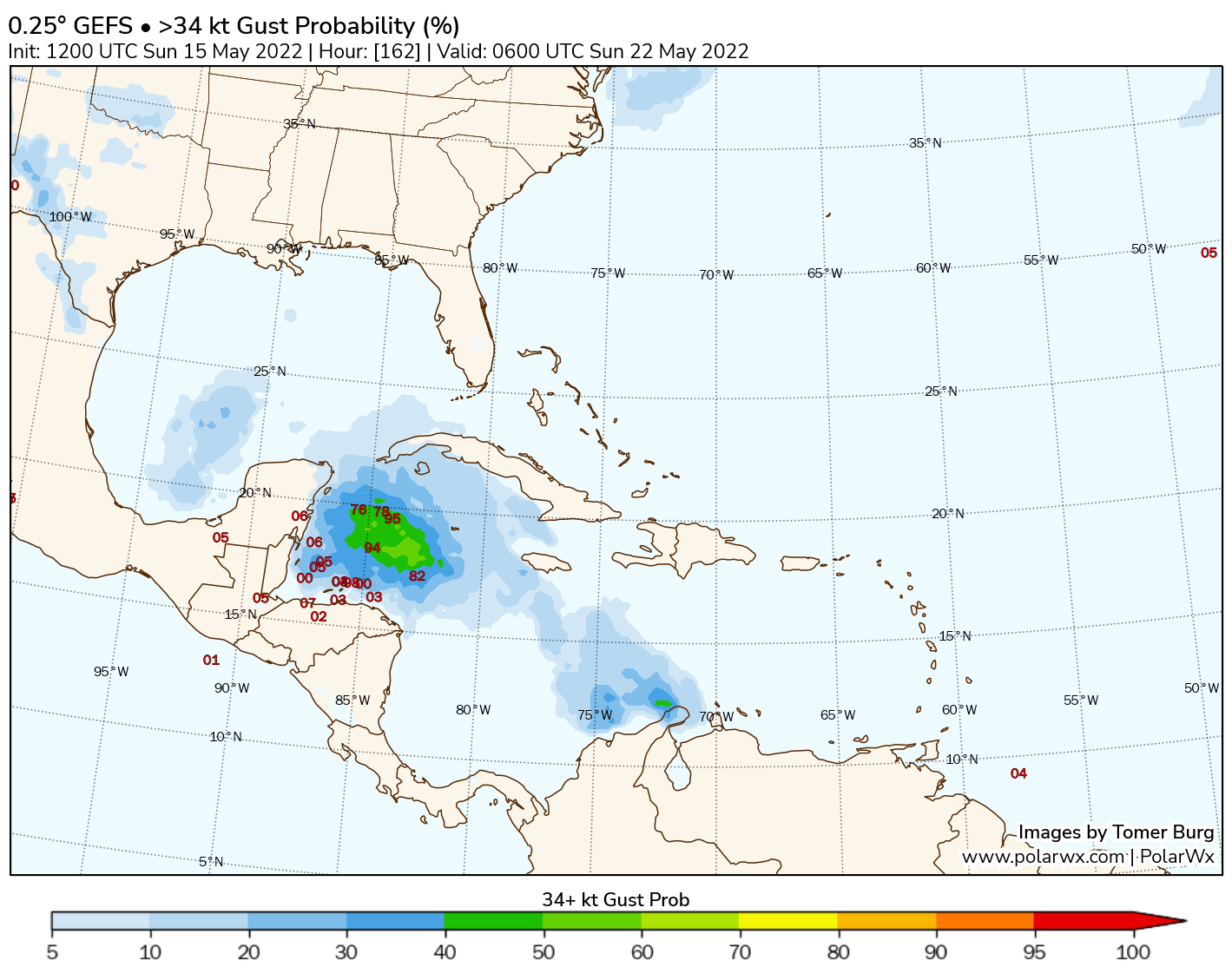

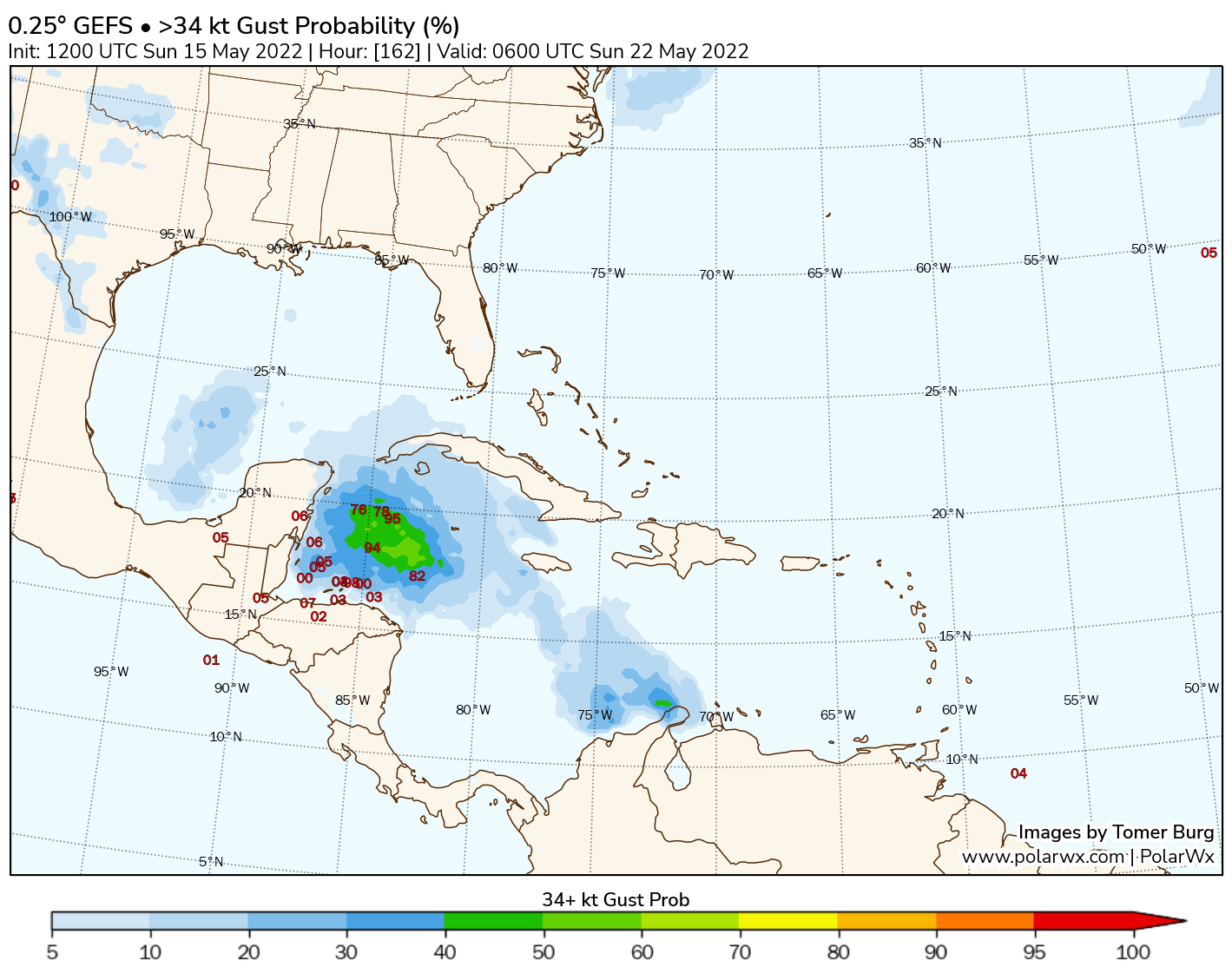

GEFS probability of wind gusts above 40 mph, and ensemble member low locations. Plot from PolarWx.

Looking at the GEFS forecast above, we see a fairly large number of ensemble members showing a weak tropical cyclone in the western Caribbean, with a small number of members showing a more intense tropical cyclone. At later lead times (not shown), just under half of GEFS members develop a hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico, while the remaining members either have a weak tropical cyclone or no tropical cyclone at all.

To better understand the GEFS forecast, we also need to understand its systematic biases. For one, the GEFS are known to have an under-dispersive bias, meaning that the ensemble spread is often too small, resulting in the true solution falling outside of the ensemble distribution. Think of this as a forecast showing the range of possible high temperature between 68 and 74 degrees, but verification is 78 degrees. The relatively recent upgrade to the GEFSv12 with an increased number of ensemble members (from 20 to 30) improved this bias, but nonetheless some under-dispersiveness remains.

Comparison of EPS and GEFS ensemble member low positions. Plot from Pivotal Weather.

Additionally, it should be noted the currently operational GFS has a higher false alarm ratio (FAR) than the previous version of the GFS, with one hotspot of FAR over the western Caribbean – the region where the GFS and GEFS show this tropical cyclone developing.

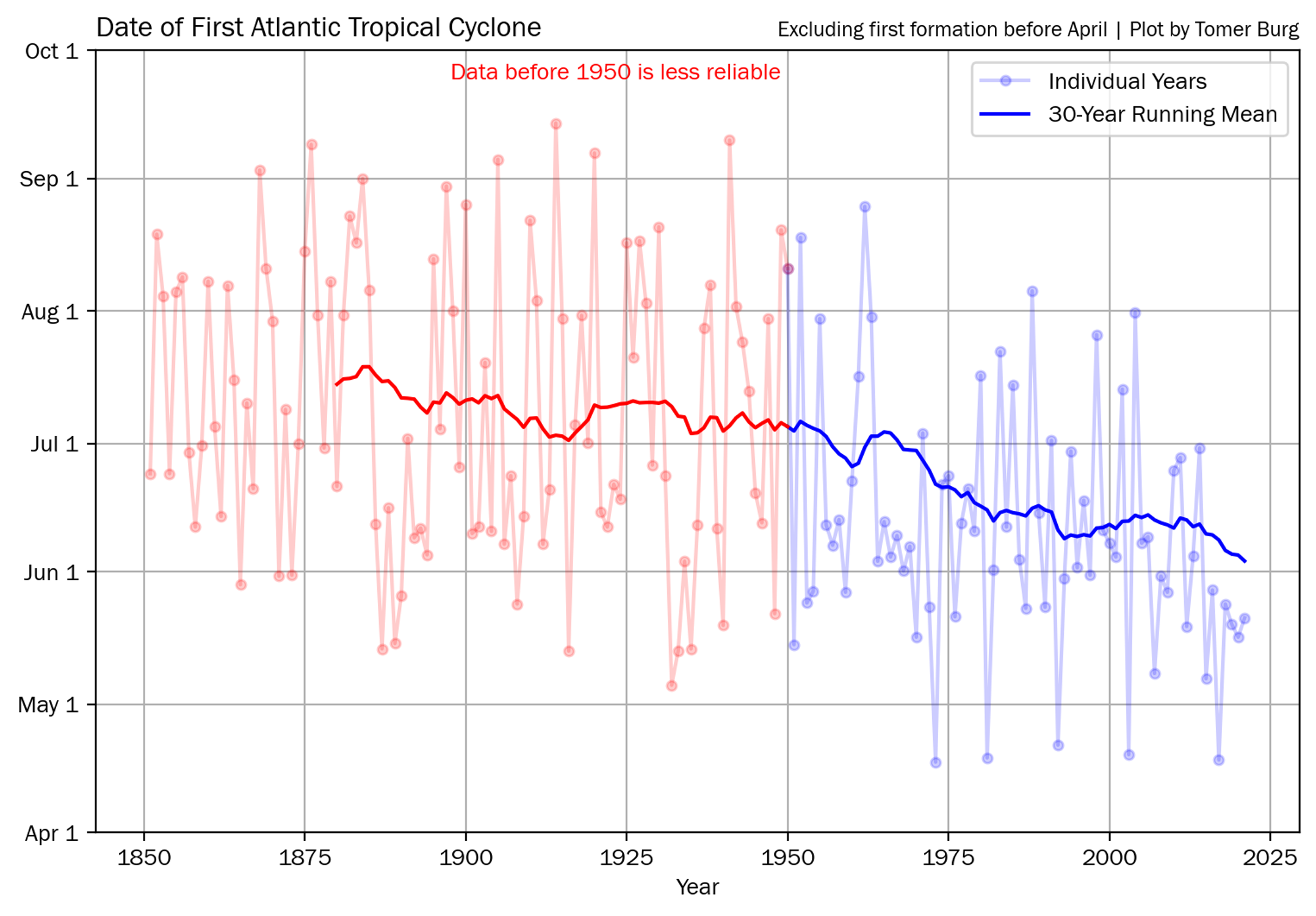

Date of first Tropical Cyclone formation in the North Atlantic from HURDATv2. Years with a storm prior to April 1st use the formation of the second tropical cyclone.

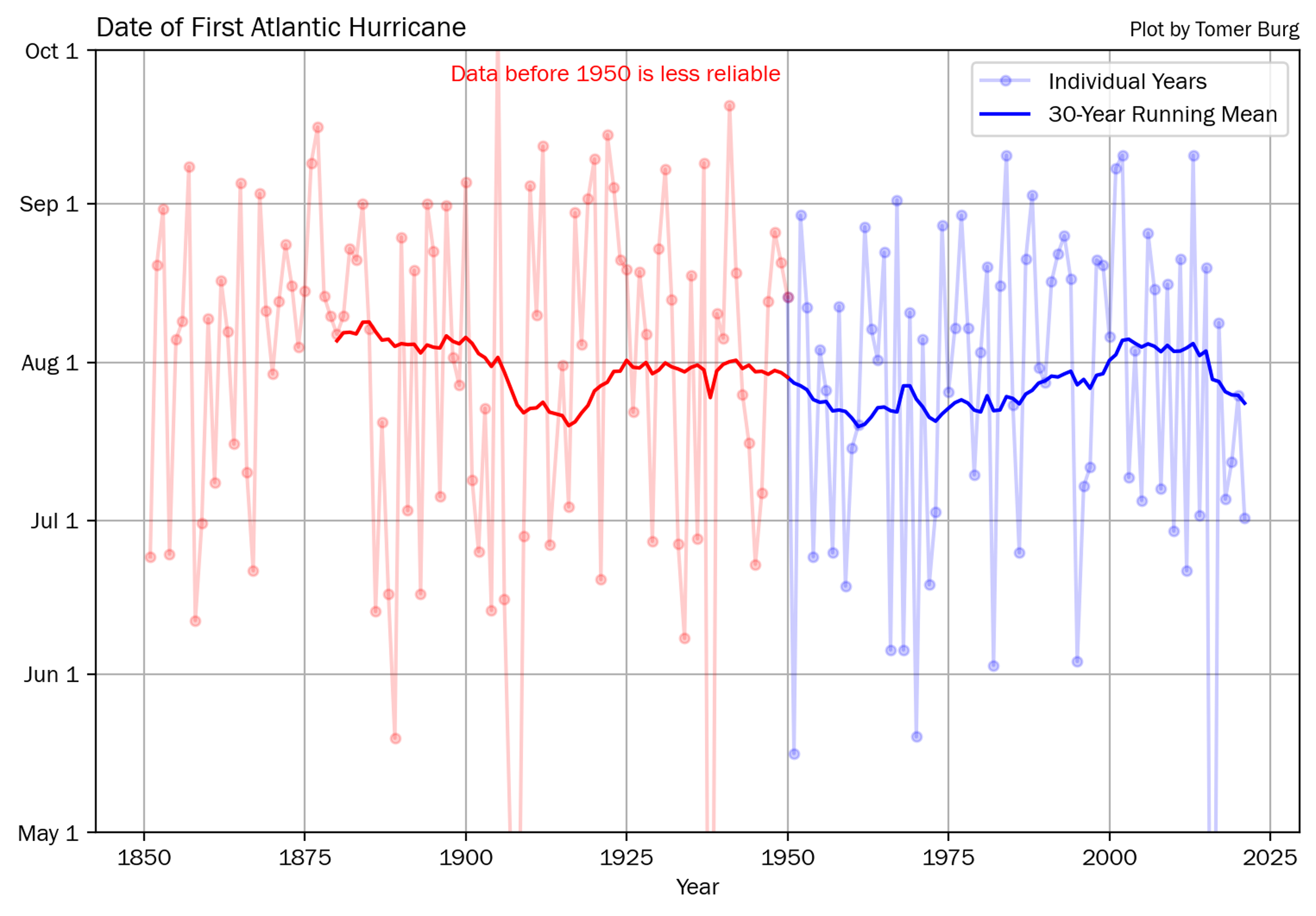

Date of first Tropical Cyclone formation in the North Atlantic from HURDATv2. Years with a storm prior to April 1st use the formation of the second tropical cyclone. Date of first hurricane formation in the North Atlantic from HURDATv2.

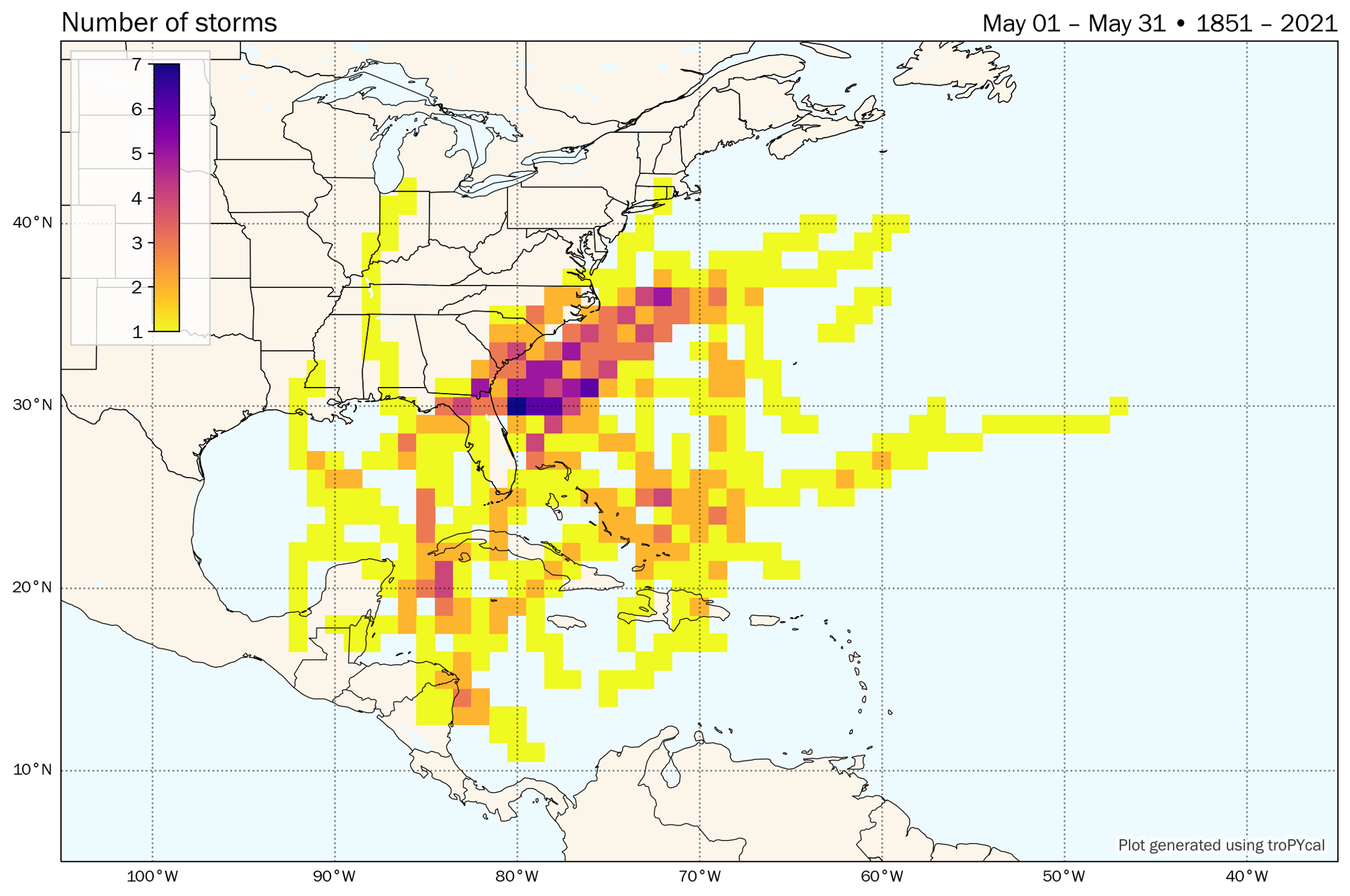

Date of first hurricane formation in the North Atlantic from HURDATv2. Number of tropical cyclones per 1 degree gridpoint in the month of May from 1851-2021. Plot made using Tropycal.

Number of tropical cyclones per 1 degree gridpoint in the month of May from 1851-2021. Plot made using Tropycal. Trend over the last 8 deterministic GFS runs in 6-hour precipitation rate and mean sea level pressure (MSLP). Image from Tropical Tidbits.

Trend over the last 8 deterministic GFS runs in 6-hour precipitation rate and mean sea level pressure (MSLP). Image from Tropical Tidbits. GEFS probability of wind gusts above 40 mph, and ensemble member low locations. Plot from PolarWx.

GEFS probability of wind gusts above 40 mph, and ensemble member low locations. Plot from PolarWx. Comparison of EPS and GEFS ensemble member low positions. Plot from Pivotal Weather.

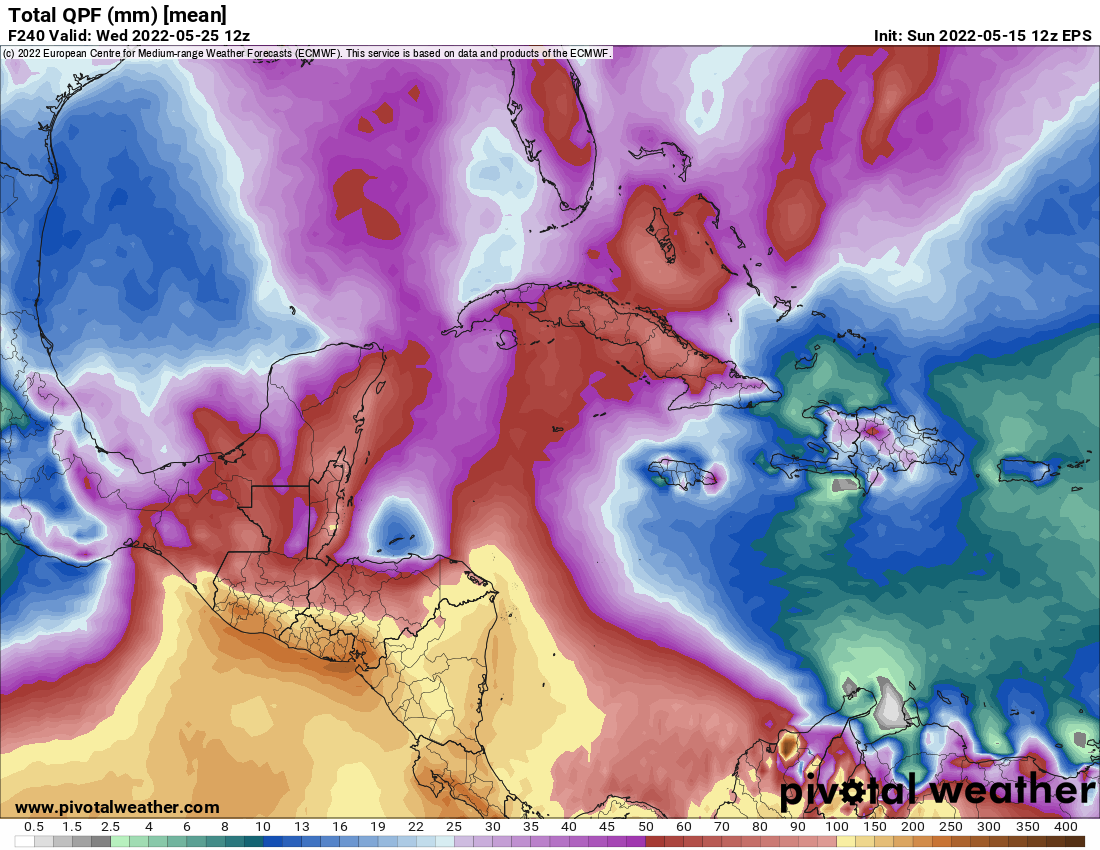

Comparison of EPS and GEFS ensemble member low positions. Plot from Pivotal Weather. EPS ensemble mean QPF (mm), valid through day 10.

EPS ensemble mean QPF (mm), valid through day 10.